Ronald Reagan and the meaning of greatness

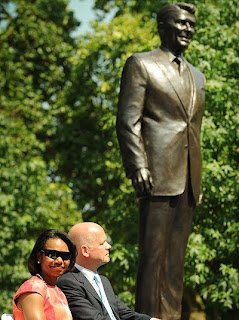

There's widespread agreement that Ronald Reagan - whose statue was unveiled in London yesterday - was a "great president". The largely positive reaction to the event comes as something of a surprise, albeit a welcome one, to someone who remembers the combination of derision and distaste in which he was held by the BBC and other parts Britain's Leftish establishment during the 1980s (if you don't remember, think George W Bush). I wonder if Lady Thatcher, when the inevitable time comes, will get such sympathetic coverage.

There's widespread agreement that Ronald Reagan - whose statue was unveiled in London yesterday - was a "great president". The largely positive reaction to the event comes as something of a surprise, albeit a welcome one, to someone who remembers the combination of derision and distaste in which he was held by the BBC and other parts Britain's Leftish establishment during the 1980s (if you don't remember, think George W Bush). I wonder if Lady Thatcher, when the inevitable time comes, will get such sympathetic coverage.But was Reagan a "great president"? And what does being a great president mean? At one level, I suppose, it means being generally regarded as great. It is, after all, an accolade given to few presidents (or, for that matter, prime ministers). Washington, Lincoln, Jefferson, FDR, perhaps Teddy Roosevelt, possibly Kennedy... after that, it's largely a matter of debate. All of these, except possibly Washington, whose eminence you'd have to be Lord North to deny, have their detractors, as does Reagan himself. Though not as many as you'd expect. Not any more.

So what makes a great political leader? Personality and achievement are both essential. A great leader has to do things of real substance, but he or she also needs to be memorable, to stand out, to have sufficient charisma (or just noticeability) to give the impression of shaping events. Roy Jenkins, in his biography of Churchill, suggests that great leaders have "strong elements of comicality in them." That goes for Churchill, of course; it also goes both for Reagan and for Margaret Thatcher. But then it also goes for Sarah Palin, so it can't be the whole story.

The most crucial ingredient of all is timing. Reagan, along with Mrs Thatcher and even Pope John Paul II, is widely credited with bringing an end to communism in the Eastern bloc. His popularity in that part of the world is largely based on that supposed achievement. Strangely, Mikhail Gorbachev, who played a more crucial (though to some extent unwilling) role in the collapse of the Soviet Union only gets credit for it in the West.

Reagan does deserve a slice of the credit. He contributed in two major ways to the undermining of Soviet Communism. His soaring rhetoric of freedom, including his talk (widely ridiculed at the time by the Left) of Russia as the "evil empire", fortified many dissidents behind the Iron Curtain and may have helped spread dissatisfaction among a wider public. It was only after Reagan had left office, though, that his rhetoric really bore fruit. He was great because he was a symbol: because he believed with a perhaps too simple faith in the greatness and goodness of America and caused others to believe it too. [Although as Alex Massie points out, Reagan's policies were often more pragmatic than his black-and-white language might have implied.]

More practically, Reagan hugely increased the US defence budget, partly by exaggerating the power and threat posed by the Soviets, in ways that the USSR was unable to match but helped to push it close to bankruptcy. The price paid was the near bankrupting of the USA itself - but Reagan was lucky, and luck is another indespensible precondition of greatness.

In the end, though, what toppled Soviet Communism was that its time was up and the Party proved itself unable to institute the necessary changes early enough, far-reachingly enough and ruthlessly enough while keeping itself in power. The Chinese communists did. Timing may have been crucial here. Mao died in 1976 and was soon succeeded by reformers; by the crucial year of 1979 the great structural revolution was underway. The dead weight of Brezhnev and his moribund successors was only lifted in 1985, by which time it was probably too late.

Winning the Cold War, though, was a long and slow process. Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon, all in their way great presidents (yes, even Nixon; perhaps especially Nixon) came too early to claim the glory. As for George Bush I, on whose watch the Soviet Union actually did collapse: he had the timing, but he lacked the charisma and, later on, the luck. As Major dwelt in the shadow of Thatcher, so was it with the older Bush - who was, nevertheless, an intelligent man, a shrewd diplomatic operator and a far better president than his son.

In the Guardian Mehdi Hasan decries the mythmakers while indulging in quite a bit of mythmaking himself. In what is rather a confused piece, his main point seems to be that Reagan was "not a Neocon", the principal evidence for which assertion is that in his day the United States was not involved in so many wars as in more recent years. The only two military actions Reagan launched were the brief invasion of Grenada in 1983 and the even briefer bombing of Libya in 1986. This is true, so far as it goes, but it doesn't really tell us anything; certainly it doesn't tell us that Reagan was "not a Neocon" - except to the extent that no-one was in those days, not officially at least.

I particularly balk at this

In contrast, consider the blood-spattered record of his successors. George Bush launched Gulf War I and sent troops into Panama and Somalia; Bill Clinton bombed Iraq, Sudan, Afghanistan and Yugoslavia; George W Bush invaded Afghanistan and gave us Gulf war II and the war on terror. And the Nobel peace prize winner Obama had troops surging in Afghanistan, launched a war on Libya and sent drones into Yemen, Somalia and Pakistan.

George Bush did not "launch Gulf War I"; Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. Perhaps Mehdi Hasan thinks that he should have been allowed to remain there. The younger Bush may have given us Gulf War II, but the war on terror had something to do with Osama Bin Laden. I realise that Mehdi Hasan prefers to deny such plain facts to their face, but they deserve a mention.

The truth, though, is that all these later conflicts were part of the aftermath of the end of the Cold War. The tearing down of the Iron Curtain was great news for the people of Eastern Europe (on balance, and for most of them) but was massively destabilising elsewhere, as the collapse of great empires, however welcome, tends to be. In a newly uncertain world, the United States found itself in the unexpected role of sole superpower, inaugurating the age of foreign intervention, of usually unwinnable wars, that is now slowly drawing to a close.

Comments