Why a decline in smoking led to the smoking ban

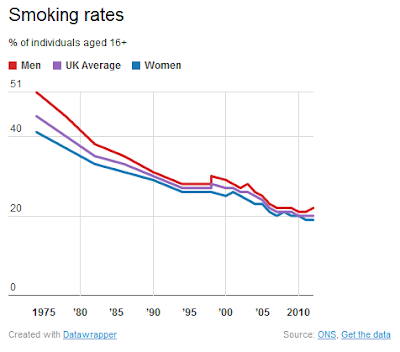

Here's an interesting graph published today by the Guardian, based on evidence provided by the Office of National statistics.

It shows the steady decline in smoking over the past forty years. Though there have been occasional blips (the most noticeable, in 1998, is apparently due to a change in the way the statistics were calculated) the direction of travel should be no surprise: from 45% of the population in the early seventies to around 20% today.

Smokers are smoking much less, too. I was also interested to discover that the threshold definition for a "heavy smoker" is twenty a day, and that only 5% of men and 3% of women come into that category. The figures for 1974 aren't offered, so I'm not sure if the official definition of "heavy smoker" has changed, but 20 a day was most people's idea of average back in the 70s. It wasn't unusual to come across chain smokers getting through as many as a hundred a day.

This is, of course, excellent news, unless you're in the life insurance business or are at all worried about the implications for pensions and social care of so many more people not dying of lung cancer and other smoking-related diseases.

You'll notice that the big decline took place in the seventies and eighties, long before the ban on tobacco advertising which was introduced in 2002, let alone the ban on smoking in public places (2006) or the introduction of graphic "warning" images on all packs in 2008. It would be hard indeed to spot any effect from any of these measures from the graph alone. It also suggests that the pearl-clutching reaction from the health lobby when the government recently shelved plans to introduce "plain packaging" for cigarettes (ie to replace branded designs with horror-movie stills showing the effect of smoking) was overdone. The likelihood is that smoking rates will continue to tail off - although, as the end of the graph shows (the part that coincides with all the recent anti-smoking measures) the decline won't be nearly as steep as it was in the 70s or 80s, or even the early years of this century. That's because the practice is now largely confined to a hard core of addicts and contrarians.

The graph neatly illustrates my longstanding principle that in public health policy the sledgehammer is only brought out once the nut has already been largely cracked. It's only when the number of smokers was reduced to a small, and increasingly unpopular, minority that it became politically advantageous to clobber them. Prior to that, the law was based on gentle persuasion (such as small-scale warnings on packets that merely informed purchasers that "smoking can seriously damage your health") along with the general background noise of official disapproval, public education and well-publicised "quit smoking" campaigns.

All this worked - or at least it coincided with a long and sustained fall in smoking. The above graph, on the other hand, shows a very slight tick upwards at the end (representing the last couple of years) among male smokers at least. Could it be that the increased intolerance of the law and the ever shriller and more apocalyptic language employed by anti-smoking campaigners is actually counterproductive? It's at least plausible that the type of person still determinedly smoking after all these years of health scares (as opposed to those who have simply failed to give up) reacts badly to the authoritarianism of bans.

The pattern revealed by the graph does, however, show something significant about anti-smoking laws. They aren't really aimed at discouraging smoking, or protecting the health of non-smokers, or even at punishing smokers (as some pro-smoking dissidents like to think). Rather, they are a form of bandwagon-jumping. Measures such as "plain packaging" are seized upon by politicians seeking to prove themselves "relevant" and up-to-date, in much the same way that they pounce upon passing moral panics or promote ideas that seem popular with focus groups. The long-term decline in smoking is a social trend for which politicians would like to claim credit. Introducing "tough" measures that can scarcely fail - because their aim has already been achieved - and which can claim to be both morally virtuous and medically justified is almost too tempting.

It shows the steady decline in smoking over the past forty years. Though there have been occasional blips (the most noticeable, in 1998, is apparently due to a change in the way the statistics were calculated) the direction of travel should be no surprise: from 45% of the population in the early seventies to around 20% today.

Smokers are smoking much less, too. I was also interested to discover that the threshold definition for a "heavy smoker" is twenty a day, and that only 5% of men and 3% of women come into that category. The figures for 1974 aren't offered, so I'm not sure if the official definition of "heavy smoker" has changed, but 20 a day was most people's idea of average back in the 70s. It wasn't unusual to come across chain smokers getting through as many as a hundred a day.

This is, of course, excellent news, unless you're in the life insurance business or are at all worried about the implications for pensions and social care of so many more people not dying of lung cancer and other smoking-related diseases.

You'll notice that the big decline took place in the seventies and eighties, long before the ban on tobacco advertising which was introduced in 2002, let alone the ban on smoking in public places (2006) or the introduction of graphic "warning" images on all packs in 2008. It would be hard indeed to spot any effect from any of these measures from the graph alone. It also suggests that the pearl-clutching reaction from the health lobby when the government recently shelved plans to introduce "plain packaging" for cigarettes (ie to replace branded designs with horror-movie stills showing the effect of smoking) was overdone. The likelihood is that smoking rates will continue to tail off - although, as the end of the graph shows (the part that coincides with all the recent anti-smoking measures) the decline won't be nearly as steep as it was in the 70s or 80s, or even the early years of this century. That's because the practice is now largely confined to a hard core of addicts and contrarians.

The graph neatly illustrates my longstanding principle that in public health policy the sledgehammer is only brought out once the nut has already been largely cracked. It's only when the number of smokers was reduced to a small, and increasingly unpopular, minority that it became politically advantageous to clobber them. Prior to that, the law was based on gentle persuasion (such as small-scale warnings on packets that merely informed purchasers that "smoking can seriously damage your health") along with the general background noise of official disapproval, public education and well-publicised "quit smoking" campaigns.

All this worked - or at least it coincided with a long and sustained fall in smoking. The above graph, on the other hand, shows a very slight tick upwards at the end (representing the last couple of years) among male smokers at least. Could it be that the increased intolerance of the law and the ever shriller and more apocalyptic language employed by anti-smoking campaigners is actually counterproductive? It's at least plausible that the type of person still determinedly smoking after all these years of health scares (as opposed to those who have simply failed to give up) reacts badly to the authoritarianism of bans.

The pattern revealed by the graph does, however, show something significant about anti-smoking laws. They aren't really aimed at discouraging smoking, or protecting the health of non-smokers, or even at punishing smokers (as some pro-smoking dissidents like to think). Rather, they are a form of bandwagon-jumping. Measures such as "plain packaging" are seized upon by politicians seeking to prove themselves "relevant" and up-to-date, in much the same way that they pounce upon passing moral panics or promote ideas that seem popular with focus groups. The long-term decline in smoking is a social trend for which politicians would like to claim credit. Introducing "tough" measures that can scarcely fail - because their aim has already been achieved - and which can claim to be both morally virtuous and medically justified is almost too tempting.

Comments